While virtually all mining accidents are preventable, there are clear patterns that identify the most common causes of fatalities in the U.S. mining industry. And depending upon which agency’s charts you’re examining, the data isn’t always easy to interpret. So, we’ll take some time to go through the information provided by MSHA related to the most common causes of mining fatalities in the U.S.

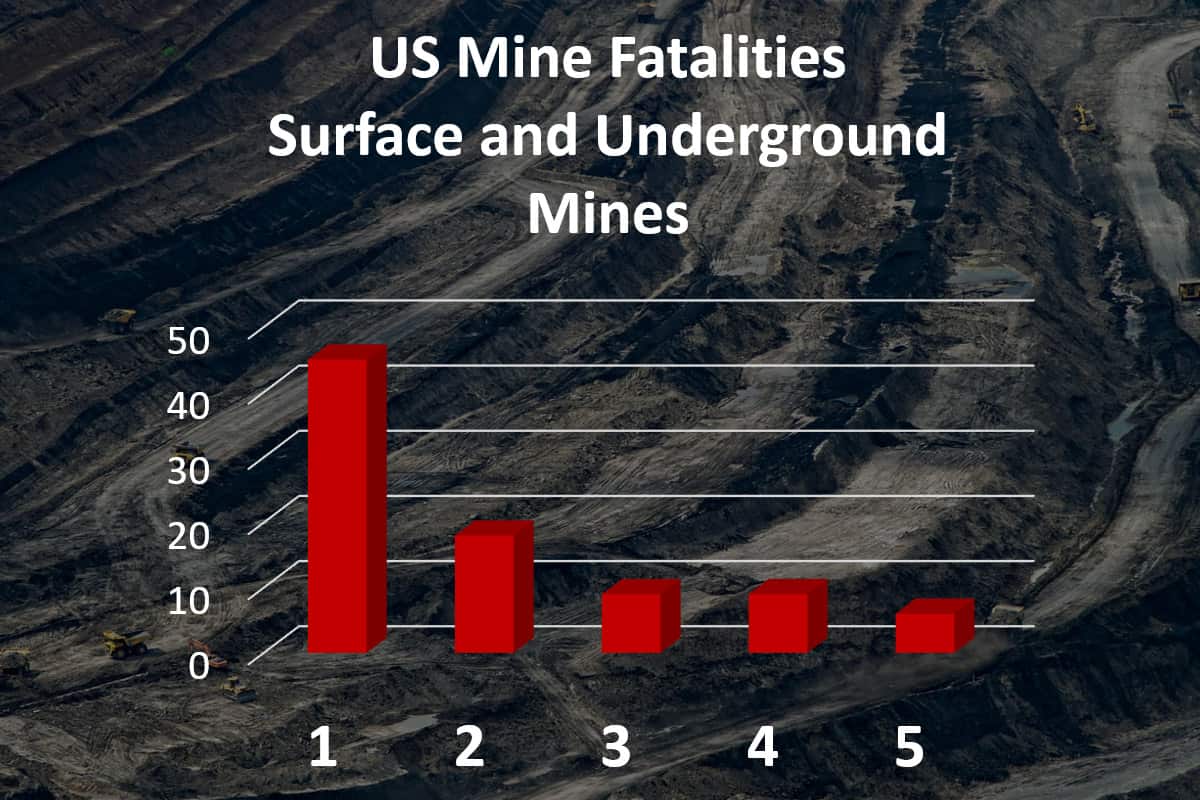

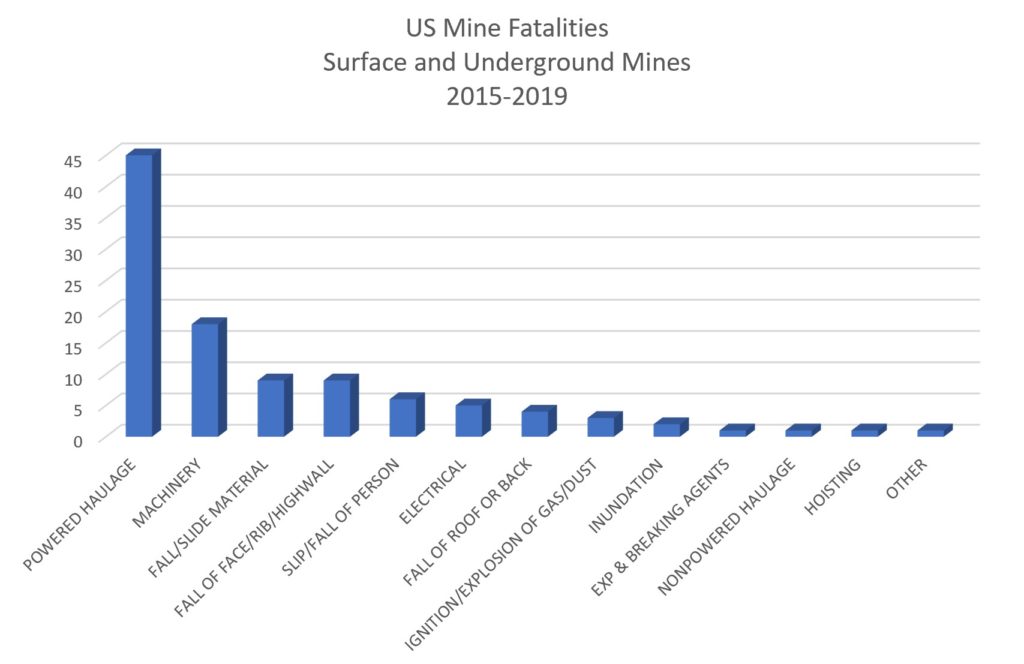

So, what are the 5 most common causes of mining fatalities? The 5 most common causes of mining fatalities are:

- Powered Haulage

- Machinery

- Falling or Sliding Material

- Fall of a Face, Rib, or Highwall

- Slip or Fall of a Person

When most of us think about life-threatening danger at a mine , we’ll likely imagine fire, explosions, and cave-ins as the most common causes. And although falling or sliding material is a commonly fatal mining accident, the more dramatic and frightening explosions are not remotely as common. While devastating and tragic explosions do occur, they are very rare. What actually tops the list of the most common mining deaths is the every-day exposure to powered haulage, things like trucks and conveyors. So, in this article, we’ll take a closer look at powered haulage and the other leading causes of mining fatalities, as well as some best practices for working safely and going home to your family in one piece at the end of the day.

MSHA Accident Reporting

MSHA uses 28 accident classifications and associated codes to document, investigate, and track mining accidents. Mine operators are required to file accident reports using the Mine Accident, Injury and Illness Report Form 7000-1. These reports and subsequent investigation results are used to determine root cause of fatalities and produce annual reports by commodity and mine type (surface or underground).

1 – Fatalities From Powered Haulage

From 2015 through Q3 of 2019, powered haulage accounted for 43% of U.S. mine fatalities. And that’s over twice the second leading cause of mining deaths (machinery accidents) for that period.

MSHA classifies powered haulage fatalities caused by:

- “motors and rail cars,

- conveyors,

- belt feeders,

- longwall conveyors,

- bucket elevators,

- vertical manlifts,

- self-loading scrapers or pans,

- shuttle cars,

- haulage trucks,

- front-end loaders,

- load-haul- dumps,

- forklifts,

- cherry pickers, and

- mobile cranes if traveling with a load, etc.

The accident is caused by the motion of the haulage unit. Include accidents that are caused by an energized or moving unit or failure of component parts. If a car dropper suffers an injury as a result of falling from a moving car, charge the accident to haulage.”

So essentially, fatalities are attributed to powered haulage in situations where a miner or mining contractor is:

- struck by,

- crushed by,

- crushed under,

- crashes while operating,

- drawn into,

- or falls from moving haulage vehicles or conveyors.

Powered haulage fatality examples include these accidents:

- At an underground coal mine on December 20, 2018, “a 35-year-old mobile bridge carrier operator with 5 years and 21 weeks of mining experience, was fatally injured when he was crushed between a bridge conveyor and a solid coal rib.”

- At an open pit limestone mine on November 3, 2018, “a 44-year-old Supervisor with three years’ experience, died…when a 150-ton haul truck ran over her parked pickup truck.”

- At a sand and gravel mine on March 8, 2016, a “haul truck driver, age 54, [with 5 years of mining experience] was [fatally injured while] operating a haul truck when it traveled beyond the dump site berm and down a slope, about 80 feet, coming to rest in 14 feet of water.”

Best Practices To Avoid Powered Haulage Fatalities

- Ensure that all appropriate engineering controls are in place, functional, and used properly.

- Ensure miners are trained on administrative controls and procedures are followed.

- Train workers on traffic control policies and the importance of following instruction on posted signs.

- Ensure equipment operators are trained to maintain control of equipment.

- Enforce use of seat belts while operating mobile equipment.

2 – Fatalities From Machinery

From 2015 through Q3 of 2019, machinery accounted for 17% of U.S. mine fatalities.

MSHA classifies machinery fatalities as related to “Accidents that result from the action or motion of machinery or from failure of component parts. Included are all

- electric and air-powered tools and

- mining machinery such as

- drills,

- tuggers,

- slushers,

- draglines,

- power shovels,

- loading machines,

- compressors, etc.

Include derricks and cranes except when they are used in shaft sinking (see HOISTING) or mobile cranes traveling with a load (see POWERED HAULAGE).”

Machinery fatality examples include these accidents:

- At a granite quarry on May 13, 2019, “a 59-year-old superintendent with 40 years of mining experience, died when the 90-ton crane he was operating fell into the quarry. [He] was using the crane to lift a section of granite weighing approximately 15 tons from the quarry when the boom started lowering. This caused the crane to tip over and fall approximately 80 to 85 feet into the quarry.”

- At a surface coal mine on October 17, 2018, “a 33-year-old auger mining machine helper (in training) with approximately 3 days of surface mining experience, received fatal injuries when he was struck in the chest while moving a piece of auger drill steel (auger steel). When he was struck, [he] was using the onboard crane in an attempt to move a piece of auger steel onto the deck of the auger machine.”

- At a surface limestone mine on September 21, 2016, “a 52-year-old Contract Drill Operator/Mechanic [with 4 years of mining experience], was fatally injured at a limestone mine while performing maintenance on a truck-mounted rotary drill. [He] was attempting to remove the spindle cap from the rotary drill using a modified pipe wrench and the machine’s drill hydraulics. When he activated the drill lever, the wrench swung in a counterclockwise direction and struck him, piercing his abdomen.”

Best Practices To Avoid Machinery Fatalities

- Ensure equipment operators are properly trained to safely operate the machinery.

- Ensure preoperational checks are performed prior to operating machinery.

- Maintain hydraulic systems to protect miners from malfunctions and system failure.

- Adhere to all safety procedures when maintaining equipment, including deenergizing, immobilizing, locking out and tagging out machinery and machine component.

3 – Fatalities From Falling Or Sliding Material

From 2015 through Q3 of 2019, falling or sliding material accounted for 9% of U.S. mine fatalities.

MSHA urges particular care in classifying fatalities from falling or sliding materials. For this accident classification, MSHA charges the force that set the fall or slide in motion with the accident. “If material was set in motion by machinery, haulage equipment, or hand tools, or while material is being handled or disturbed, etc., charge the force that set the material in motion. For example, where a rock was pushed over a highwall by a dozer and the rock hit another rock which struck and injured a worker – charge the accident to the dozer. Charge the accident to that which most directly caused the resulting accident. Without the dozer, there would have been no resulting accident. This includes accidents caused by improper blocking of equipment under repair or inspection.”

Falling or sliding material fatality examples include these accidents:

- At a surface dimension granite mine on October 11, 2018, “a 26-year-old laborer with approximately one year of experience at the mine, was fatally injured, while performing secondary breakage operations on a block of granite. [He] was standing on a previously sawed slab of granite, attempting to further separate the slab from the highwall. He fell between the slab and the highwall when the slab broke free.”

- At a surface coal operation on August 3, 2017, “a 32-year-old surface preparation plant mechanic with 12 years of mining experience, received fatal injuries while he was dismantling a 1,400-pound water box associated with the rotary filter. The water box fell and struck [him], pinning him to the floor.”

- At a surface open pit sand mine on March 14, 2017, “a 52-year-old customer truck driver [with 13 years of semi-truck driving experience] was fatally injured when he exited the cab of his tractor trailer, walked to the rear of the trailer, and was engulfed by sand dumped from his trailer. The accident occurred because the victim entered the area behind the raised trailer bed while unloading concrete sand material.”

Best Practices To Avoid Falling or Sliding Material Fatalities

- Ensure that work is performed from a location that does not expose miners to dangers of secondary breakage.

- Always examine ground conditions

- Provide adequate task training

- Enforce use of fall protection

- Ensure sufficient blocking and cribbing supports are used to prevent motion of equipment and machine components during maintenance and repair.

- Always stand clear of material being unloaded, dumped onto a pile, or scaled from a rock wall.

4 – Fatalities From Fall Of Face, Rib, Or Highwall

From 2015 through Q3 of 2019, fall of face, rib, or highwall accounted for 9% of U.S. mine fatalities.

MSHA classifies fall of face, rib, or highwall fatalities as related to “falls of material (from in-place) while barring down or placing props; also pressure bumps and bursts. Since pressure bumps and bursts which cause accidents are infrequent, they are not given a separate category.

Not included are accidents in which the motion of machinery or haulage equipment caused the fall either directly or by knocking out support; such accidents are classified as machinery or haulage, whichever is appropriate.”

Fall of face, rib, or highwall fatality examples include these accidents:

- At a surface coal mine on December 11, 2018, “a 38-year-old surface miner with 14 years of mining experience, was fatally injured when a large portion of a highwall (approximately 7,000 to 8,000 cubic yards) toppled, crushing the operator’s cab of his front-end loader. [He] was operating the front-end loader to remove blasted material near the base of a 63-foot highwall.”

- At a surface limestone mine on July 25, 2016, “[a 59-year-old equipment operator with 17 years of experience] was killed when rock from a highwall, approximately 80 feet above, fell on the operator’s cab of the hydraulic excavator that he was operating.”

- At an underground coal mine on January 16, 2016, “a 31-year-old continuous mining machine operator with 13 years of experience was fatally injured when he was struck by a large section of the mine rib. The victim was operating a remote-controlled continuous mining machine…when a large portion of the right side rib fell pinning him to the mine floor, causing fatal crushing injuries.”

Best Practices To Avoid Fall of a Face, Rib, or Highwall Fatalities

- Conduct adequate daily ground condition examinations to identify potentially hazardous conditions before beginning work near a highwall.

- Train workers to adhere to highwall inspection procedures.

- Take down or support hazardous ground conditions before commencing work in a highwall area.

- Provide pre-shift rib inspections and roof control plans, including adequate supports of mine ribs.

- Provide mine examiners with adequate training on hazard identification and corrective actions.

5 – Fatalities From The Slip or Fall of a Person

From 2015 through Q3 of 2019, the slip or fall of a person accounted for 6% of U.S. mine fatalities.

MSHA classifies slip or fall of a person fatalities as related to “slips or falls from an elevated position or at the same level while getting on or off machinery or haulage equipment that is not moving. Also includes slips or falls while servicing or repairing equipment or machinery. Includes stepping in a hole.”

Slip or fall of a person fatality examples include these accidents:

- At an open pit limestone mine on March 7, 2019, “a 46-year-old contractor with three years of experience, died… after falling 12 feet from the top of a log washer. While [he] was tightening bolts on the log washer drive motor, his wrench slipped off the bolt head, causing him to lose balance and fall backwards. He fell through an approximately 16-inch gap between two log washers, striking a handrail before landing on an electrical cable tray. He suffered internal injuries and died at the hospital.”

- At a surface coal facility on February 27, 2017, “a 43-year-old plant attendant with 13 years of mining experience, received fatal injuries when he fell through an opening in a plate press. The victim was preparing to make repairs to the plate press when he fell onto a moving conveyor belt, which moved the victim to a transfer chute 55 feet from where he fell.”

- At a magnesite quarry on September 15, 2016, “[a 60-year-old mechanic with 20 years of experience] was injured while working on a front end loader. [He] had completed his assigned tasks and was dismounting the machine when he fell. He impacted the ground with his head, neck, and shoulders and was unconscious for several minutes. He was transported to [the hospital] and placed on life support. [He] died as a result of his injuries on September 26, 2016.”

Best Practices To Avoid Slip or Fall of a Person Fatalities

- Establish and enforce a compliant “working from heights” policy.

- Train personnel on the proper use of fall protection.

- Ensure that miners use fall protection where there is a danger of falling.

- Train miners on accessing ladders and steps and maintaining three points of contact with mounting and dismounting equipment.

- Provide additional guard rails and guarding where there is a risk of falling off or into equipment.

- Deenergize, lockout and tagout all machinery in a work area where there is a risk of falling into otherwise operating machinery.

A Note About Fatality Information

At times, it may be easy to overlook the fact that each of these examples of fatalities are drawn directly from actual reports of miners suddenly and unexpectedly losing their lives. These are not just data points. They’re American men and women who didn’t go home to their families that day. And while their passing rarely makes the news equivalent of a mine explosion or large-scale disaster, their loss of life was no less impactful to their families and communities. We display this information with great respect for those who died and the hope that the results of their accident investigations and the associated corrective actions will help continually reduce the loss of life in the mining industry.

Related Questions

Which is More Dangerous, Underground or Surface Mining?

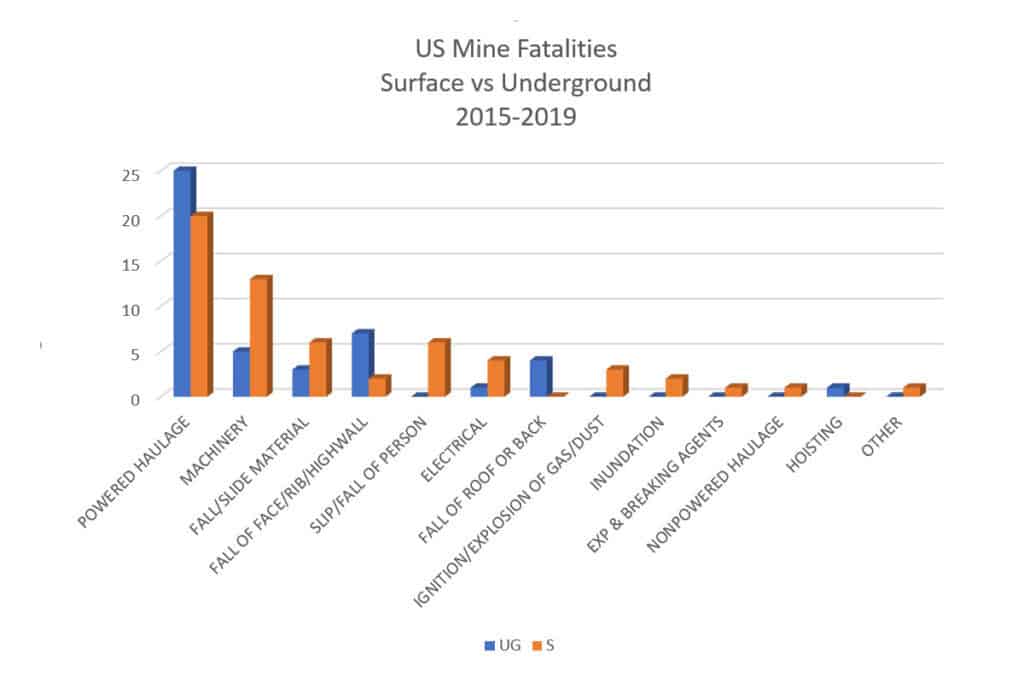

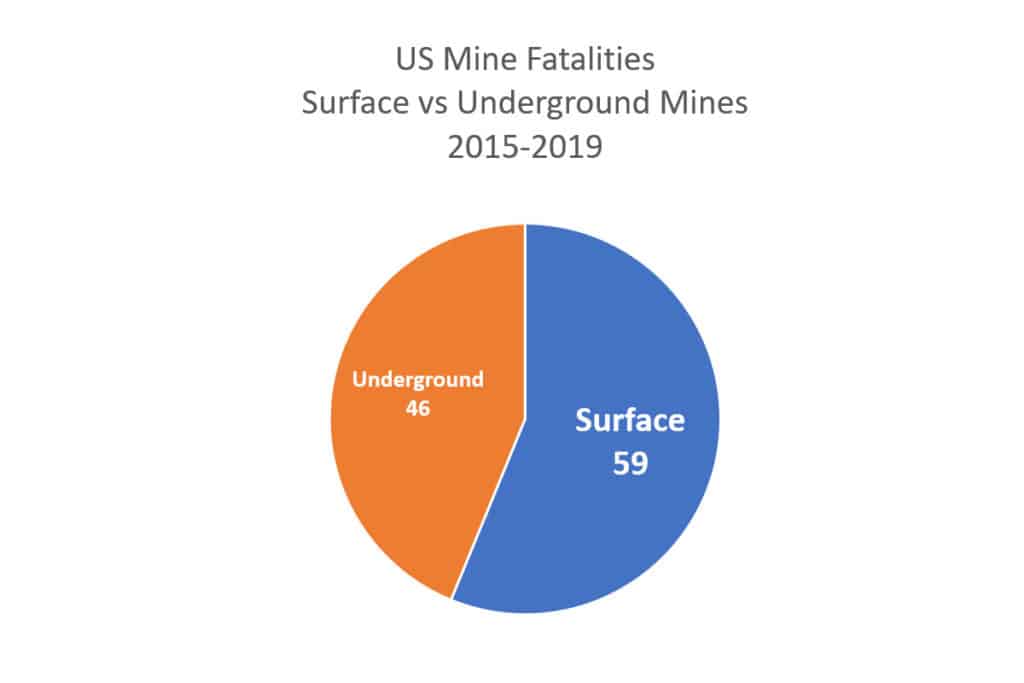

From 2015 through Q3 of 2019, surface mines accounted for 56% (59 deaths) of U.S. mine fatalities, while underground mines accounted for 44% (46 deaths) of mine fatalities.

While Underground mines accounted for 25% more powered haulage fatalities, surface mines accounted for 160% more machinery fatalities and all fatalities from the slip or fall of a person.